The Last Movie at HOME

Tom Grieve, Cinema EditorBook now

The Last Movie

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

“That’s what’s wrong: we brought the movies.”

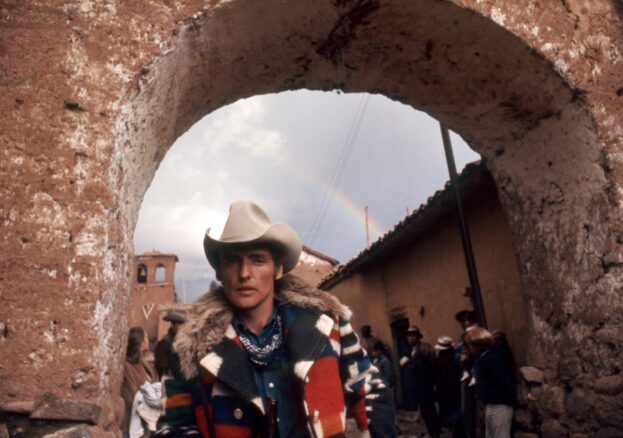

Difficult to see for so long, Dennis Hopper’s 1971 The Last Movie arrives at HOME courtesy of a pristine new restoration. In the wake of the runaway success of Easy Rider, Universal famously handed Hopper a million dollars and asked for more of the same. What they got was a messy, debauched vision of post-hippy aimlessness set at a fictional movie location in remotest Peru. Elusive and frequently maddening, The Last Movie takes aim at ideas of masculinity, America and at the corrupting power of industrial cinema. It was far from the hip, existential road movie that had made so much money. Despite winning the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival, the suits were decidedly unimpressed and the film came to symbolise the worst of New Hollywood indulgence.

Working on both sides of the camera, Hopper stars as Kansas, an American stuntman and horse-wrangler working on a Hollywood western being filmed in a small village in Peru. Lines are blurred by the casting of filmmaker Samuel Fuller as the director, and Peter Fonda and Kris Kristofferson in minor parts. The production dominates the town but one day the filming finishes, and the cast and crew leave. Left behind are the sets (a cheap facsimiles of a cowboy town), and Kansas, who decides to stay on with his Peruvian girlfriend, Maria (Stella Garcia.) Before long, the locals take to imitating the Americans, faking cameras out of wood and beating each other up for phantom lenses. Kansas is called in to explain the art of stage fighting; “We fake everything. It’s all phoney,” he tells them.

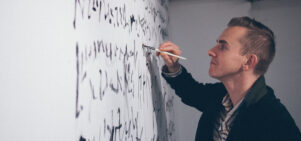

While village life slowly disintegrates, Kansas sinks into madness and the bottle. Hopper fragments his story, inserting “Scene Missing” cards and hallucinatory elements. There’s an uncomfortable, boozy sequence in which Kansas and some traveling Americans visit a local brothel, whilst a absurd sojourn to the site of a prospective goldmine turns up nothing. The chaos on screen was matched off it, as filming overran, and the splintered, subjective edit took an age. The fact that the set was reportedly overrun with cocaine and questionable behaviour further blurs the lines between realities, on screen and off.

The re-release of The Last Movie should go some way to release it from its reputation. As with Michael Cimono’s Heaven’s Gate, Hopper’s film is revealed today as more than an indulgent New Hollywood curio. It is a disturbing portrait of self-obliteration and a personal odyssey into ‘70s movie-making, deepened by the way its narrative mirrors the chaos of its production. Despite veering close to cultural condescension (it is almost 50 years old), The Last Movie is a canny commentary on the unsettling tentacles of capitalist America’s soft power. It might leave you dazed and confused, but from today’s vantage point, Hopper’s claim that is his magnum opus doesn’t look too far off.