Ericka Beckman and Marianna Simnett at FACT

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions EditorVisit now

Ericka Beckman and Marianna Simnett

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

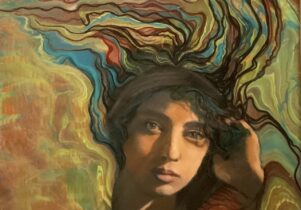

From the grey-faced, boil-nosed wicked old witch to the youthful and virtuous(virginal) fair maiden adorned in white, fairy tale archetypes provide powerful expression of the ways in which women and their bodies have been labelled and controlled throughout the centuries. Yet it is the question of how these age-old stories (evolved out of earlier oral traditions) intersect with the position of women today that interests and unites the work of eminent American filmmaker Ericka Beckman and rising London-based video artist Marianna Simnett.

Their upcoming duo-exhibition presented at FACT marks a strong start to the organisation’s year-long season focusing on female-identifying artists responding to themes of identity, representation and gender. The show will be accompanied by an extensive public programme of talks, live events, films and workshops exploring gender, female archetypes and fairy tales.

Though Beckman and Simnett’s output is very different in style, both create surreal and disturbing fantasy worlds within which they seek to dismantle and subvert patriarchal ideology, whilst also considering the role of science and technology within this contemporary narrative.

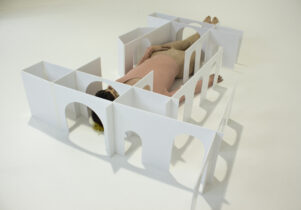

Since she first began making films in the 1970s, across her ongoing career Beckman has used the logic of early gaming to fashion sardonic rewrites of classic tales, through which she seeks to explain the “social systems and learned behaviours that we’ve ingested through media.” FACT’s exhibition will feature her simultaneously comic and disturbing Cinderella (1986) and Hiatus (1999), in which the female protagonist in both is trapped – never able to fully satisfy the demands of the ‘game’ they are in.

Winner of the 2014 Jerwood/Film and Video Umbrella Award, Simnett creates fable-like film, performance, sound and light installations that seek to unravel the binary ideas we still hold around subjects such as gender, desire, health and morality. Often featuring unflinching depictions of needles, blood and medical interventions that the artist has undergone herself, her work also examines the ways in which the female body has been treated throughout history as a site for clinical experimentation in the name of science and progress – areas that (Simnett argues) have come to replace the societal role that fables and stories once played as sources of truth and wisdom.

Beckman and Simnett make for a powerful pairing, and the positioning of their work alongside each other should provide a remarkably rich perspective on many of the key cultural issues that have come to preoccupy our present time.