Child Labour: Hidden Stories of Cumbria at Museum of Lakeland Life & Industry

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions EditorBook now

Child Labour: Hidden Stories of Cumbria

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

In relation to the sharp rise in child labour in England during the 19th century, brought about by the Industrial Revolution, and the terrible work conditions that many children as young as five faced, it’s often smog-filled urban centres like Manchester (nicknamed Cottonopolis) that form the backdrop to our popular imagination. But what about the experience of working children in more rural regions, like the Lake District?

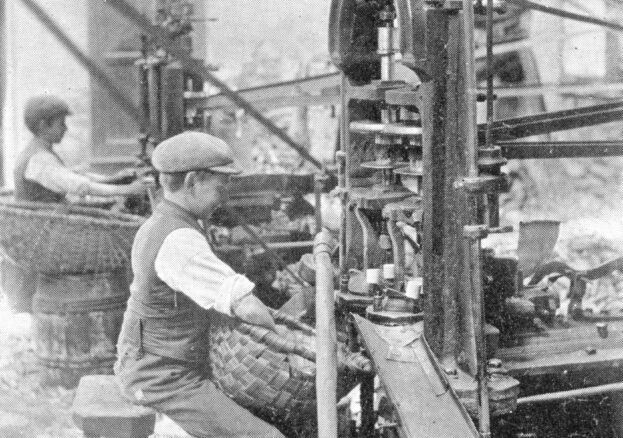

Children were used to perform dangerous tasks such as crawling beneath the machinery to clear dirt.

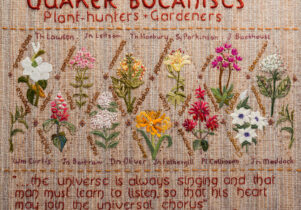

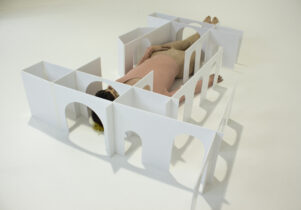

A new exhibition at Museum of Lakeland Life & Industry departs from this question, documenting the changing conditions in youth employment from the 1700s onwards. At one point, Cumbria was home to more than 100 bobbin mills, where children were used to perform dangerous tasks such as crawling beneath the machinery to clear dirt, dust or anything else that might disturb the mechanism. The district was equally an important mining centre, and young boys were typically responsible for minding trap doors, picking out coals at the pit mouth, or carrying picks for the miners. Again, this was by no means a safe environment and in 1910 an explosion and fire the Wellington Pit in Whitehaven led to 136 deaths. Many children worked on farms and in private homes, too, where they were frequently subject to acts of extreme and systematic violence from their employers.

In addition to these experiences, Child Labour – Hidden Stories of Cumbria also considers how life for children changed during the period as laws were eventually passed towards the end of Queen Victoria’s reign making it compulsory for them to remain in education until the age of 12 and restricting the amount of factory hours that could be worked.

A reflection upon how much life has changed for children over the past 300 years, and how desperately change is still needed.

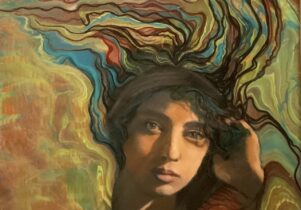

Today, access to education and freedom from exploitation are considered basic universal rights under international law. Yet, according to Human Rights Watch, over 70 million young people around the world remain trapped in sectors such as agriculture, mining and domestic labour, often working extremely long hours under hazardous conditions for very little or no pay. The part of the museum draws attention to this fact, encouraging visitors to reflect upon how much life has changed for children over the past 300 years, and how desperately change is still needed in some areas.

Expanding visitors’ understanding of child labour both in terms of the historic and present-day, within a local and international context, this eye-opening exhibition is not to be missed.