Bigger than Life presents/ Beau Travail at HOME

Tom Grieve, Cinema EditorBook now

Bigger than Life presents/ Beau Travail

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

When Moonlight director Barry Jenkins declared Claire Denis “the greatest filmmaker on the planet”, he was echoing a sentiment shared by many cinephiles. An artist preoccupied with Denis returns to cinemas this month with High Life — her first film fully in the English language. Starring Juliet Binoche and Robert Pattison, the disturbing, sexually-explicit science fiction film has been making waves since its Toronto debut. A high-concept work, High Life follows a group on convicts sent into space, it finds Denis, as ever, exploring humanity through bodies, sex and taboo.

To mark the film’s release, local film organisation, Bigger Than Life, have organised a 35mm, twentieth-anniversary screening of Denis’ most acclaimed film: Beau Travail. At first, the earthy, desert-bound Djibouti setting of Beau Travail seems, quite literally, a million miles from High Life’s out-of-this-world premise. But, as writer Ellen Smith remarks in her programme notes, Claire Denis has frequently “addressed ideas of foreignness, identification, and colonialism on Earth”, and there’s only a short leap from the isolated French Foreign Legion troop depicted in Beau Travail to the deep-space convicts of High Life.

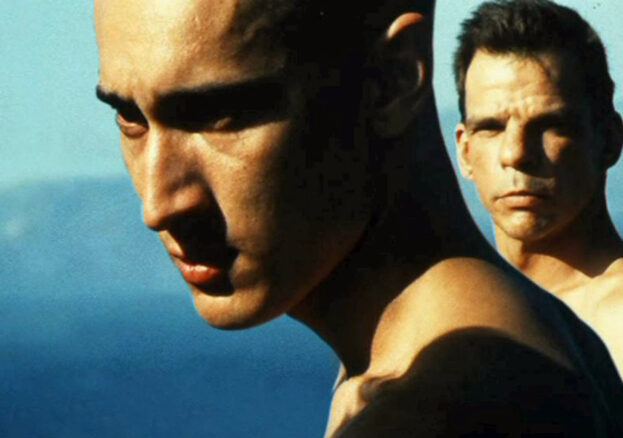

Beau Travail has grown in stature since its 1999 release, to the point where it features consistently on lists of the greatest films ever made. Loosely based on Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd, Beau Travail stars Denis Lavant as a disgraced French Foreign Legion sergeant-major who recalls his time in the Horn of Africa. As is to be expected from Denis, there is a focus on texture and movement. Working with regular cinematographer Agnès Godard, she lingers on skin and salt, capturing the strange codes and rituals of the Legion. Conflict arrives in the form of an enigmatic new recruit (Grégoire Colin), who sparks intense feelings of resentment and jealousy in his superior.

The daughter of a French diplomat, the director grew up in various parts of West Africa, and her work is often concerned with key themes of repression, colonialism and masculinity. Here she engages with all three, contrasting scenes of the legionnaires engaged in punishing training – which the director films sensuously, almost as ballet – with their excursions to local towns and nightclubs. The film itself is overwhelming, relying upon sensation and ellipsis to place viewers in its remote landscape, and communicate the dark compulsions that drive soldiers into the anonymity of the legion.

Any mention of Beau Travail would be inadequate without reference to its final shot, which stakes a claim as the best in all of cinema. It’d be criminal to spoil here, but suffice to say that the rhapsodic grace note set to Corona’s club classic “Rhythm of the Night” is worth the price of admission alone.