Visual Rights at Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions EditorVisit now

Visual Rights

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

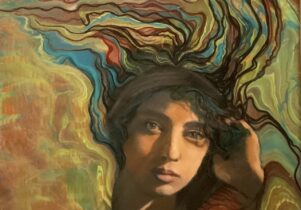

The complex range of forces that exert power over us is vast, from the media, economics, corporate interests and the law, to societal attitudes, our physical surroundings, and even the use of language, to name just a few examples. But what does power look like? How can we visualise it in a concrete sense? A new exhibition at Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool departs from this question, bringing together the work of six artists from Palestine, Israel, and the UK who use photography as a tool to expose the ways in which power subtly operates and affects people’s lives, and to reveal its unequal distribution.

Visual Rights is curated by photographer, sociologist and academic, Gary Bratchford, and approaches its subject through the lens of territorial conflict; one of the most ancient and profound ways in which power has shaped the world. For this reason, much of the work in the show focuses on geographical boundaries, borders and aerial surveillance. Miki Kratsman and Shabtai Pinchevsky, for instance, present their grassroots project Anti-Mapping, which creates high-resolution documentation of places that have been obscured or removed from the public map, such as combat training zones for the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF), destroyed Palestinian villages, and unrecognised Bedouin villages.

Also taking to the skies, Restricted Zone: Temple Mount by Hagit Keysar uses a drone to capture the technological and civilian restrictions over the aerial space in Jerusalem by testing the no-fly zone (NFZ) surrounding Temple Mount, or al-Aqsa; a site that has become the heart of a religious and political conflict. Another project by Keysar examines how aerial photography can be used by citizens to provide human rights testimony against discriminatory spatial and political practices.

Other artists in Visual Rights explore questions of power from the ground-level. Tarek Al-Ghoussein’s series of images refer to the ‘Green Line’ (a border established in 1967 to mark out the separation between Israel and Palestine that has been contested ever since), and Corine Silva’s Garden State project considers how gardening, like mapping, is used to divide and allocate territory, photographing public and private gardens in twenty-two Israeli housing settlements. Meanwhile, Yazan Khalili employs electricity as a visual metaphor. His long-exposure photographs capture the contrast between the night sky over the Palestinian town of Birzeit, where the artist stayed under an Israeli government curfew in 2002 and which was frequently thrown into darkness during power cuts, and the brightly illuminated towns made visible from across the border.

Collectively, Visual Rights offers a striking look at how power shapes the lives of those living in one of the world’s most troubled regions, whilst also raising broader questions around freedom and control in the 21st-century.