William Kentridge: Thick Time at the Whitworth

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions EditorVisit now

William Kentridge: Thick Time

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

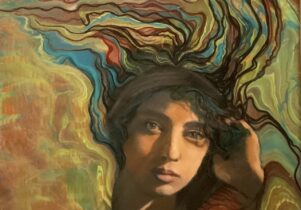

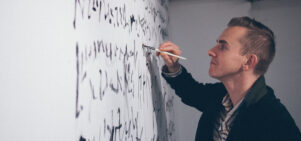

Born in 1950s Johannesburg to a pair of lawyer-parents both famous for their defence of victims of apartheid, the work of internationally celebrated artist and serial collaborator William Kentridge is fundamentally shaped by the issues of racial segregation and oppression that have long over-shadowed South Africa, explored within a global context of 20th century revolutionary politics and utopian aspirations. His 40-year-long career has spanned a startling diversity of art forms – including large-scale musical dramas and opera-design as well as sculpture, tapestry, collage and installation – yet he remains best known for the animated films that first led him to prominence in the 1990s featuring his deeply poetic, expressionistic charcoal drawings.

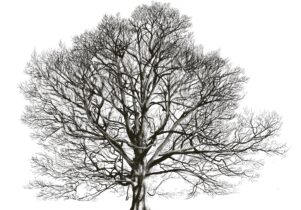

Using a characteristic stop-motion technique, Kentridge brings these drawings to life for his viewer – following each from its moment of genesis, with the invisible draughtsman’s first stroke, through a journey of evolution as the image begins to take shape and eventually crystallises, only to be rubbed out and reborn upon the palimpsest of the canvas in another form. It is this unfurling sequence (a kind of distillation or concentration of temporal process) that Kentridge refers to as ‘thick time’ – the title of his major internationally touring exhibition which arrives at the Whitworth this September after calling at Whitechapel Gallery (London), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (Humlebaek) and Museum der Moderne (Salzburg).

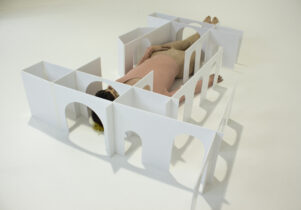

The meaning and expression of time forms a running thread throughout Kentridge’s work, as examined at length in The Refusal of Time (2012) – an immersive audio-installation piece which delves into the technology of time-keeping and string theory, created in dialogue with physicist Peter Galison. The Refusal forms one of five moving image works that will be presented at the Whitworth, and will be shown within an environment designed by Kentridge’s long-term collaborator Sabine Theunissen alongside a broad selection of studio drawings, sculptures, music, projection and two new large-scale tapestries.

Though such philosophical themes as the nature of time may appear to sit oddly with the somewhat less abstract anti-imperialist and anti-colonial concerns that underpin Kentridge’s work, this breadth of content is in fact characteristic of the artist. The wider exhibition draws on sources as wide ranging as early cinema, China’s Cultural Revolution, opera, scientific theories of space, and the generative qualities of nature and creativity. The result should prove to be both mind-boggling and fascinating in equal measure.