Dean Kenning: Evolutionary Love at Bury Art Museum and Sculpture Centre

Maja Lorkowska, Exhibitions EditorVisit now

Evolutionary Love

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

This winter, Bury Art Museum and Sculpture Centre is the temporary home to the Mark Tanner Sculpture Award travelling exhibition Evolutionary Love, hosting the 2020/21 recipient of the Award, artist Dean Kenning.

The award is described as the most significant award for emerging artists working in the field of sculpture in the UK. The criteria for the works which make it to the final stage are: a particular interest in work that demonstrates a commitment to process and sensitivity to material. Dean Kenning ticks both boxes, with his semi-autonomous, moving robot sculptures.

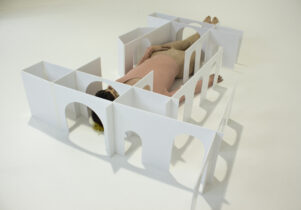

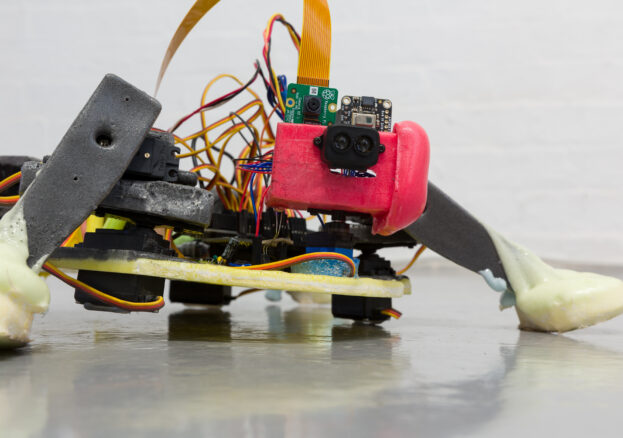

The works on display were made from elements of re-engineered obsolete technology alongside materials that resemble a more organic humanness, like wax and foam. The robots were programmed with the help of creative computing educator and coder Llewelyn Fernandes. The resulting ‘creatures’ crawl around on the floor, unsteady but certain of wanting to avoid collisions with each other and audience members. Their size resembles that of a small animal, tall enough to bite your ankle, while each ‘creature’ is armed with a camera, so that point-of-view footage can be live streamed on screens mounted just above the floor, forcing the viewer to come closer to the ground in an effort to better understand the view from the robots’ perspective.

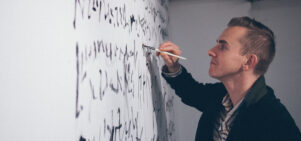

Dean Kenning is an artist, researcher and lecturer whose oeuvre focuses on DIY processes, diagrams, the uncanny and the humorous. Kinetic sculptures are a common occurrence in his creative musings, along considerations of machine autonomy and the concepts of sympathy and empathy

Indeed, the animalistic robots in Evolutionary Love stemmed from thinking about the idea of love, rather than self-interest, being the main driving force behind evolution which challenges the Darwinian survival of the fittest. Published in an essay by Charles S. Peirce (which the title of the exhibition was taken from), this idea was explored in-depth in the 19th century and inspired Kenning to ask: ‘Can the audience feel sympathy for these obviously mechanical creatures?’ The robots aren’t created in batches, each one possesses slightly different characteristics: one has two legs, the other four, one moves quickly and decisively while the other one seems to consider its movements. It is these differences that bring them closer to that all-too-human element of unpredictability and is perhaps the source of their eerie charm.

Frankensteining human elements with machine parts may not be a revolutionary idea but its element of the uncanny never fails to unsettle. Take a trip to Bury Sculpture Centre to meet these creatures yourself and decide – can we, to an extent, empathise with a machine?