Soldiers of ink and paper

Matthew Hull

Blogs and social media applications like Twitter and Audioboo are undeniably transforming journalism, but nowhere is this change happening more quickly than in the coverage of conflict. What better time for an exhibition examining the history of war reporting? Matthew Hull heads to Imperial War Museum North for a first look.

Most of us will be lucky; we will never experience war firsthand. Our images of war – troops pushing the flag into the sands of Iwo Jima; helicopters rising from the embassy building in Saigon – are the ones printed on front pages or beamed into our homes. Our understanding of conflict is shaped, then, by those who report from the frontlines. War reporting outrages, saddens, and inspires us. It was one of William Howard Russell’s battlefield dispatches from the Crimean War for The Times which moved Tennyson to write “The Charge of the Light Brigade” while, more recently, the Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker was based on the account of embedded journalist Mark Boal.

A new exhibition opening at Salford’s Imperial War Museum North sheds light on the work of war journalists over the past century using a range of artifacts, images and recordings. War Correspondent: reporting under fire since 1914 is built on the experiences of twelve seminal war reporters from across the 20th and into the 21st century; from Philip Gibbs’ reports from the trenches of World War One through John Simpson’s coverage of the conflict in Afghanistan.

Among the unique items on display for the first time are a Reuters Land Rover partially destroyed by a rocket in Gaza and the iconic white suit worn by BBC war correspondent Martin Bell – a look he adopted completely by accident, according to Josephine Garnier, researcher and curator at IWMN. “After covering the Gulf War he refused to wear military uniform again. So while reporting on the Bosnian war he happened to have his white suit with him and so it became his trademark. He can be quite superstitious and has ascribed his continued survival to the suit,” she said. “I think, in a way, he felt invincible wearing it.”

One of the most moving pieces in the exhibition is the recording of Richard Dimbleby’s broadcast from the liberated Bergen Belsen concentration camp which ably illustrates the importance of the work these reporters do in bringing the crimes of war to the attention of the public – often risking their lives to do so. “Dimbleby was a stoic and professional man yet he could not help but be overcome by the horror of the situation, “Garnier said. “The BBC actually didn’t believe the reports when he initially filed them and refused to broadcast them. But he insisted and said that he would resign if they didn’t put them on air.”

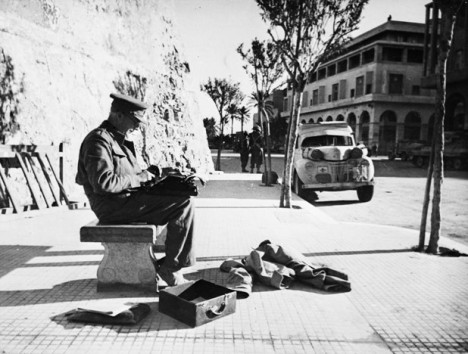

Alongside recorded testimony from well-known names like Kate Adie and Rageh Omaar are some modern audiences may not be as familiar with, like Martha Gellhorn (aka Mrs. Ernest Hemingway), whose reports on the Spanish Civil War were the first to focus on war’s impact on the lives of ordinary people.

Of course in recent times there has been a monumental shift in the way news is created and consumed – if you have an internet connection you can instantly find out what is happening anywhere in the world; if you have a camera on your mobile phone you can report on it yourself.

“We’re experiencing the death of old-style journalism,” Garnier says. “The whole idea of reporting has become very fluid. The uprising in Syria, for example, isn’t being widely covered by correspondents who are stuck over the border. Instead the news is coming from a wave of citizen journalists; bloggers and social media users living inside the country. It’s completely different from the way people received news about the Second World War or even the Falklands. So, for me, there is no better time to look back and see how the conflicts that changed the world were reported to us.”

War Correspondent: reporting under fire since 1914, to 2 January 2012, Imperial War Museum North, The Quays, M17 1TZ. Free.